a genealogy of my aesthetic; 20 films.

Hal Hartley’s Flirt (1995)

While PJ Harvey was belting out “You're Not Rid of Me” on her first EP, in another more fictionalized New York, Bill has to decide if he'll promise himself to Parker Posey, who at 7pm is flying to Paris, France. He'll give her an answer by 5 o'clock, but not before consulting a Brechtian chorus in the men's bathroom: it’s important to keep the girl in your influence at all times! and: the best of all possible approaches to this dilemma is for the both of you to firmly embrace reality! After, Bill is shot by the embittered husband of his (other) current girlfriend.

Like all Hartley film, the dialogue is delivered in a style simultaneously sweet and staccato; a language simplified like song lyrics, somehow both ambiguous and piercing. This story cycle repeats in Berlin and then Tokyo—the German version with a gay interracial fashionista and the Japanese tale told entirely in silent Butoh. If it sounds overly pretentious, don't worry, Hal already knows: "The filmmaker wants to ask if the same situation played out in different times amounts to anything different," a construction worker ponders in second person in somewhere-platz, "but he's already failed."

Success, humility, failure, or good filmmaking: it doesn't much matter. Hartley has stated that this is his favorite of his films. It’s personal: it ends with a shot of him holding a canister of 35mm motion picture film, labeled "Flirt,” collapsed and despondent from the act of repeating and constant movement. But, he's found by Miho Nikaido, the Japanese protagonist played, who later becomes his wife...you know, in real life.

Mood: open-hearted, wondrous, everything-is-gonna-be-alright

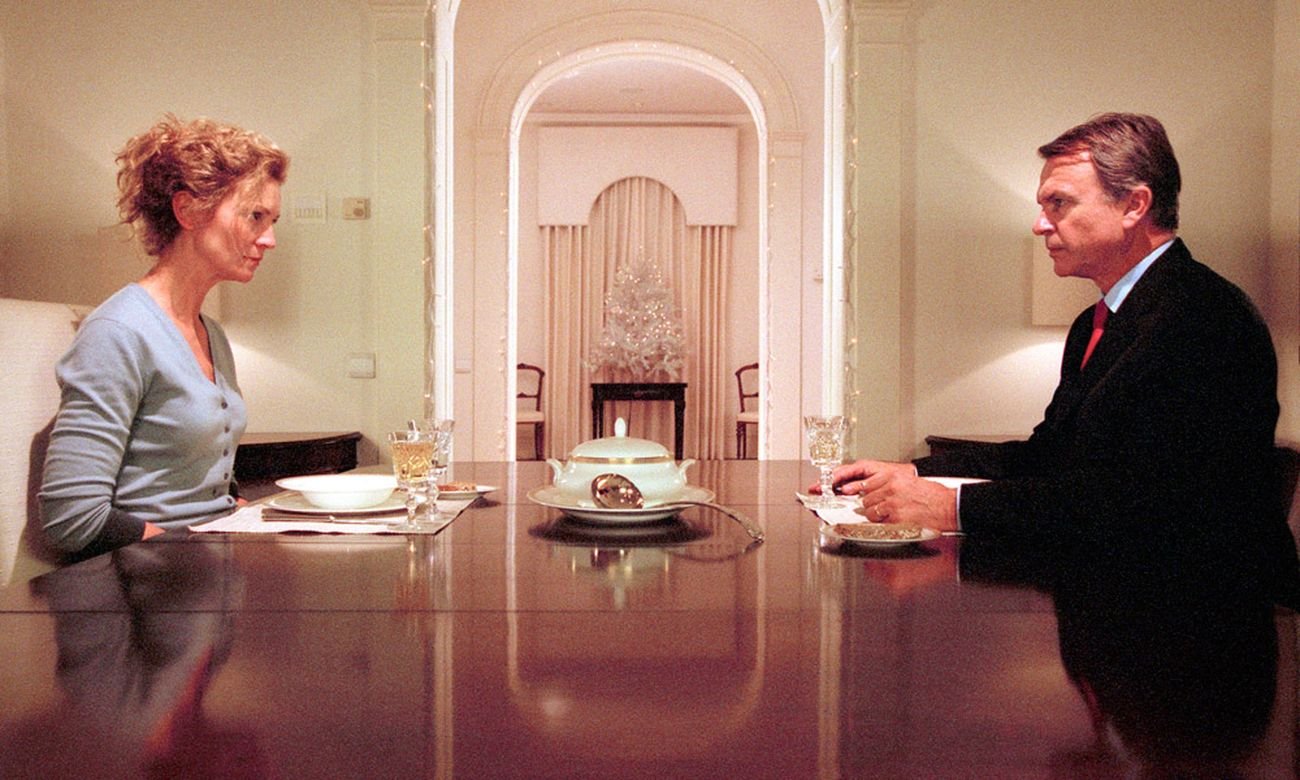

2. Sally Potter’s YES (2004)

Sally Potter started to write YES on September 12, 2001. It is a meditation on inter-cultural love told entirely in iambic pentameter; for this, it has been ruthlessly mocked as trying to be overly artsy. For me, the language flows seamlessly. More distracting are the very early 2000s cinematography choices (the diagonal angle, the shaky hand-held with jump-frames). But, I can forgive all these and still find the experiment worthwhile and even satisfying.

She—as her name is never revealed—is an Irish-American scientist; He was a doctor in Lebanon but now uses knives in restaurant kitchens. They say Yes to each other while her marriage is collapsing; she’s in a gala-gown and he’s in a waiter’s suit, clowning and catching her giggles. Later, he fingers her in a cafe while she repeats yes, yes, yes. Let all things hidden be exposed. Yes. Let all things become pleasure. Yes. I’m going to make you cum. Yes.

There is an incredible scene where she visits her grandmother in Belfast, an old unconscious radical who telepathically commands her grand-daughter I want my death to clean you out! The film was made between 9/11 and the American invasion of Iraq; and, there’s this strange moment in the “making of” short film that’s always haunted me: the two main actors are with director Potter going over lines when suddenly, Joan Allen (She) breaks down crying about Bush’s press conference, the launch of the war against Saddam Hussein. Allen is crying out of (American) guilt, Potter consoles her, while Simon Abkarian (He) is stranded.

Mood: calamitous global politics don’t have to stop us from loving

3. Atom Egoyan’s Calendar (1994)

“Only Armenians know this movie!” an Armenian Turk told me. But, Egoyan is Canadian-Armenian, with equal emphasis on both, as so much of his filmography is about the tension of being in a diaspora, and the lengths people go to feel belonging.

Egoyan seamlessly weaves themes of digital (dis)connection, diasporic loss, sex work as psychological therapy, and the use of repetition as (un)comfortable catharsis. The protagonist is deeply masochistic, continually devising a form of cuckolding not based in fucking, but a much deeper addiction to cultural alienation.

Mood: doesn’t it feel so right to watch your wife fall in love with someone else, you sub, nostalgic lil’ bitch

4. Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married (2008)

This is such an Obama-era movie. How can I back that up? See the upper-“middle class” East Coast family all dressed in Indian Saris for a cross-cultural wedding; gathering and not fighting about politics. They have enough trauma to wade through as Anne Hathaway’s character, Kym, cannot forgive herself for an accident that ripped the family apart years ago. This is one of the most honest representations of 12-step processes I’ve ever seen. This is also exactly how most weddings in my community feel: artistic family reunions.

I saw this in high school and it also introduced me to the genius musician Robyn Hitchcock, who I’ve now seen live twice.

Mood: what if your wedding vows were a Neil Young lyrics?

5. Patrice Chéreau’s La Reine Margot (1994)

Based on a novel of the Saint Bartholomew’s Days Massacre by Alexander Dumas, La Reine Margot features Isabelle Adjani as Marguerite de Valois, forced into a fake-peaceful marriage to unite the Huguenots and the Catholics in 16th century France. The real star may be Catherine de Medici, played like a great literary villain. But, it should be noted that Catherine was well celebrated for her festivals that are unmatched and maybe unimaginable today; the film tries to express this lavishly.

The score by Goran Bregović is incredible, bringing an oddly refreshing Eastern European feel to the stale form of the French period piece.

Mood: everyone is power is a pervert

6. Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (1979)

How dare you call another man on my phone who’s not gay!

Inspired by Fosse’s own heart problem that kept him bed-ridden, the protagonist of All That Jazz is addicted to amphetamines, cheating on his wife and girlfriend, and choreography. A time-capsule of the 1970s New York Broadway scene is also a musical about (ego) death with Fellini-esque motifs. Jessica Lange stars as the seductive angel of death taking Joe Gideon on a tour of his trauma, pleasures, and haunting mistakes. This is my mom’s favorite movie, who shared it with me at probably too young an age.

Mood: a dark cabaret dance number about an airline specializing in emotionally-empty orgies; “our motto is, we take you everywhere but get you nowhere.”

7. Gregg Araki’s Nowhere (1997)

Lucifer, you’re so dumb you should donate your brain to a monkey science fair!

This film has been a litmus test for anyone I’ve dated; if they didn’t get it, I knew things would be hard down the line. I’ve gone to some version of Juji-Fruit’s party so often in New Orleans, and even though this is an exploration of teenage (queer/punk) desperation in the ‘90s, it feels very true to my contemporary life in Louisiana. The protagonist Dark is looking for a more traditional love in this mess of poly-traumatic-high-saturated-horror mediated via some late night 1-900 ad or just static colorbars. Araki’s ending asks if radical subcultures are any less Kafkaesque than the “normie” world. The set design and art direction by Patti Podesta is a constant inspiration.

Mood: hey, shouldn’t you be in thermo-nuclear catastrophes class?

8. Scott Campbell’s Off the Map (2003)

Everybody gets depressed, why should you be above it, huh?

As much shit as I talk about Albuquerque, the truth is that New Mexico, the land itself—the way the sun hits without diffusing humidity, the smell of piñon burning in winter, and the endless sky—is incredibly magical. Off the Map is the film that epitomizes that beauty, showing how this landscape affects the social human realm. Based on a domestic-based theater piece, it’s a memoir of young Bo, a precocious girl who cannot wait to shed her rural poverty and be an office worker with a briefcase (and, one not from the dump). Joan Allen is the star; holding the piece together effortlessly as embodying a subtle indigenous grounding to their communing with the land.

Mood: human beings are part of nature

9. Michael Haneke’s Code Unknown (2003)

Montre-moi ton vrai visage!

Haneke is a master of the long take. He explains this in a making-of segment for The Piano Teacher, saying that it gives actors the space to play out a scene fully, and allows them to ride the wave of an emotional process fully. He repeats these takes mercilessly until the actors do something that surprises themselves—a shriek, a gesture from out of nowhere, a completely improvised action.

Code Unknown opens with a group of deaf children playing charades. Then, a long take on a Paris street that ends with the arrest of a North African and the deportation of a perceived Romani woman. The film continues on fragments of these characters from this single shot. There is a character—the war photographer—based on Luc Delahaye, the father of my friend, Mathilde Delahaye (an incredible theater-maker, herself).

Mood: we are all implicated in power structures; we are all responsible even if we want to believe our innocence

10. Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve (1950)

“I walked into my dressing room and said “Good morning,” and do you know what [Bette Davis] said back to me? “Oh shit, good manners.” I never spoke to her again—ever.” co-star Celeste Holm.

“Working on All About Eve was a tremendously enjoyable experience—the only bitch in the cast was Celeste Holm.” —Bette Davis

What can I say? I am super gay. And the script for All About Eve basically invented the catty queen, every line is just so juicy and satisfying. Part of a series of 50s flicks that questioned “the golden age of”—in this case, theater—it was a radical piece for its time.

Mood: every word of my seething breakdown will be a-nun-ci-ated, darling.

11. Gurinder Chadha’s Bend It Like Beckham (2002)

“Get your little lesbian feet out of my shoes!” / “Lizbian? I toaught she vas a Pisces!”

It’d be lying if I didn’t include this feel-good movie made almost entirely of musical montages of early 2000s club hits; Now That’s What I Call Cultural Understanding Vol. 4 — some previous South Asian-white (gay) romance hits being Chutney Popcorn (1999) and My Beautiful Laundrette (1985). It’s a shame that the original lesbian overtones were erased; but the inclusion of the hollow romance with Jonathan Rhys-Meyers is really gay in some odd way. Probably one of my all-time favorite bad movie lines is when he tries to console protagonist Jesminda after she receives a racist slur: “Jess—of caurse I know how that feels! I’m Ay-rish!”

Mood: Me? Kissing? A boy!? You’re mad, you’re all bloody mad!

12. David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999)

“I have to play eXistenZ with somebody nice. Are you nice?”

Once you get through the longest opening credits sequence since 1959’s Ben Hur, you’ll find yourself in a small town rec-center where Allegra Geller is unveiling her brand new virtual reality video game. Everyone is porting into the fleshy console through their bio-port, a small opening at the bottom of their spines. “Death to the Demoness, Allegra Geller!” Suddenly a young boy shoots Geller with a gun made of teeth while she’s minimally conscious of “reality” — as much a statement of how consumer-media affects our sense of self and surroundings, the dialogue is also an implicit critique of Hollywood script structures. It was inspired by the declaration of fatwa on Salman Rushdie; and it’s probably the first time “non-playable characters” were poked fun of. Pay attention to Geller’s hair.

Mood: am i in a coma? did i win the game? did i win?

13. Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion (1985)

Trailer narrator: “Never before have two adults consented to so much.”

I struggled to pick just one film from Ken Russell—the trashier English Federico Fellini who I truthfully love more. There’s the respectable “Women in Love” from 1969, incredible with Glenda Jackson; there’s his response to Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman with 1991’s “Whore,” a second-person monologue about the reality of sex work; there’s his outlandish musical bio-pics of Tchaikovsky and Mahler. I landed on Crimes of Passion simply because it includes a husky voiced Kathleen Turner introducing herself as “China Blue” while a red light constantly flashes in her nasty in-call space. There’s a priest with a metal vibrator that becomes a dagger. It’s Russell at his most sexually absurd.

Mood: Anthony Perkins can only play psychos, but this time there’s good good steamy sex and dildo murder

14. Ming Tsai Liang’s The Hole (1999)

The Hole makes claims about intimacy by subtracting it completely; the only relief in this abysmally depressing grey cloud of a film are musical numbers of Cantonese covers of 1950s American songs. A pandemic has shut down Taiwan; two apartment tower dwellers (minimally) deal with one another while a hole grows larger and larger between one’s floor and another’s ceiling. Tsai Liang is a master of slowness; he once filmed someone crying for half an hour; this piece is as relaxing as it dis-affecting, and totally dissociative.

Mood: in the mood for love, minus the love, minus the mood. add the smell of mold.

15. Cameron Crowe’s Vanilla Sky (2001)

“I almost died, and you know what—your life flashed before my eyes.”

As much as I would like to say I enjoyed Alejandro Amenábar’s original 1997 film “Abre los Ojos” more, I just didn’t. Maybe it’s because I’m a maximalist, maybe it’s because the inclusion of hyper-pop-culture made different statements here, maybe it’s Crowe’s overly sentimental style—it’s certainly not because of Tom Cruise. But, honestly, he does a good job here. This was one of my favorite films when I was a teenager, so even if I should abandon it for more high-brow selections, I’ve just seen it too many times to not acknowledge it’s influence on me: for one, maybe it is Julie Gulianni I eroticize as I’ve fallen for femme after femme fatale who threaten to take me on their suicidal plans; I certainly hope I will wake up at any moment, but while I’m here, the soundtrack is pretty great.

Mood: what do you think of my music? it’s vivid!

16. Sophie Muller and Annie Lennox: Diva (1992)

“Now, everyone of us is made to suffer! Everyone of us was made to bleed!”

Is it a stretch—including one of the first video albums? I don’t care: I have to credit Sophie Muller’s stunning filmography of music video production and her collaborations with so many 90s feminist icons—Lennox, Courtney Love, Gwen Stefani, Sinead O’Connor, PJ Harvey. She was inventing forms of femininity that were mediated out through MTV, adopted by young women across continents. In this huge achievement for Lennox’s first solo album, the two craft personas and poke up at the production of persona, either as pop star, lover, home-maker. They had already worked together creating the video album for the Eurythmics album Savage; that work is also incredible, but it didn’t get into me when I was a child like this one did (thanks, Mom).

Mood: it’s called diva

17. Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991)

Its very rare that any film-maker gets to accomplish their dream project as a first feature, let alone a woman, let alone a black feminist who was Charles Burnett’s contemporary. Narrated by the future daughter of one of the protagonists, the film is a lyrical and impressionistic telling of the Gullah people in the early 20th century, when the pressure to move to the mainland (not coastal South Carolina, but towards Chicago and New York) was strong. Even though the community retains a near-total control and black autonomy on their islands, they are still haunted by slavery, colonialisms, and threats to their livelihood. Dash was clearly aesthetically influenced by Peter Weir’s “Picnic at Hanging Rock” from 1975; and, they have a strange kinship, even though Weir’s entire cast is lily-ass white, the film is just as haunted by colonial ghosts and the power of land to (take) hold of us.

Mood: soul-affirming, family bonds as historical struggle

18. Harvey Feinstein’s Torch Song Trilogy (1988)

I think my biggest problem in life is being young and beautiful. Oh, I’ve been beautiful! God knows I’ve been young—but never the twain have met…

This is a gay touchstone for me; it’s the romantic comedy turned tragedy turned fights with Jewish mother movie I needed to understand what queerness past might’ve been like. The film is based on Feinstein’s play from 1982 which mostly chronicles gay life of the 1970s, hence why HIV makes no cameo in this story. There’s even an acceptance of bi-sexuality, certainly not a common practice then by gay male scenes; Matthew Broderick is the no-drama boyfriend every queen desperately needs and doesn’t deserve.

Mood: heart-warming; family is not based in blood-ties

19. Pedro Almodovar’s Mujeres al Borde de un Ataque de Nervios (1988)

Take me back to the hospital, that's my home!

I make a really great gazpacho; it’s not at all the recipe from this movie that is recited maybe 12 times. It’s actually more of a salmorejo: a smooth creamy emulsion of tomato and olive oil with sherry vinegar, sugar, salt, and smashed garlic with stale bread. Once, I made it for a dinner party and a friend said “You are so fucking gay, I can’t handle it!” So, here’s to the gays and our gazpacho! At least my party didn’t culminate in multiple barbiturates, forlorn love triangles, and a twiggy-brunette holding a gun to our heads. This is Almodovar giving himself full permission to be a high camp queen.

Mood: wigs on motorcycles with guns

20. John Greyson’s Lilies (1996)

Forgive me, Father—I’m about to commit the sin of revenge.

I have more than a high tolerance for experimental productions resulting in less-stellar works. Like Sally Potter’s “The Gold Diggers,” which was the only film to be made entirely by women and explored inter-race/class feminism, “Lilies” is made entirely by gay men. “Lilies” comes after Greyson’s musical about the HIV crisis, “Zero Patience,” in which Sir Richard Burton is brought to contemporary times to stage an anthropological exhibition on the AIDS “patient zero.” Greyson would later be imprisoned in Egypt for preparing work on a film centering Gaza activism; this is all to say: Greyson is a film-maker comrade. And, with “Lilies,” he let that militancy relax slightly to create a theatrical period piece mise en scene akin to Marat / Sade. He still wants to light the Catholic church on fire, though there is a conclusion of mutual understanding.

Mood: a gay man in drag as Julie Taymor does shadow puppets in prison